Why are there different versions of the Bible? Highly documented

When the early church began, it had no holy book other than the Old Testament. The followers of Christ did not separate from the Jews at first, as it is stated in the Gospel of Luke 24:53: “And they continued to attend the temple, praising God” after the ascension of Christ to heaven.

There is no conclusive evidence as to when the books that make up the New Testament were written or who wrote them with certainty, but manuscript scholars have their own opinions and interpretations on this issue. Most of the style of these scholars and researchers in Christian manuscripts contains words such as perhaps, probably, and most likely.

For example, see the following page:

When the ****** began, there were no New Testament books. Old Testament texts alone were used as scripture. The first book written was probably I Thessalonians (c. 51) (or possibly Galatians which may be c. 50-there is some controversy over the dating of Galatians). The last books were probably John, the Johannine epistles, and Revelations toward the end of the first century

The name New Testament did not appear until the end of the second century, as the introduction to the ecumenical French translation of the twelfth Beirut edition states:

“It was not customary to call this collection the New Testament until the end of the second century, as the writings that compose it gradually attained a high status until they became as important in their use as the texts of the Old Testament, which Christians considered for a long time to be their only holy book .”

It is known that the New Testament consists of twenty-seven books that took its current form through a long and complex history, and these books, that is, the books that make up the New Testament, were not considered sacred texts until a long time after the ascension of Christ. The introduction to the French translation states:

“Before the beginning of the second century, there is no evidence to prove that these texts were considered sacred books with the same importance as the Holy Book.” On page 3 it says:

“And about the year 150 a decisive period began for the formation of the New Testament canon. Justin Martyr was the first to mention that Christians read the Gospels in Sunday meetings and that they considered them to be the writings of the apostles (or at least the writings of people closely connected to the apostles) and that when they used them they gave them the same status as the Holy Bible . See the website

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/first_apology

St. Augustine (a theologian from the second century) said the following:

“On the day called Sunday, all those in the cities and villages gather in one place where the memoirs of the apostles are read to them,”

meaning that these writings were called the memoirs of the apostles

. “ And on page 4 of the introduction to the French translation it says:

“There are also works that were customarily cited at that time as being from the Holy Scriptures , and thus part of the canon, and they did not remain in that state for a long time. Rather, they were finally removed from the canon. This is what happened to the book of Hermas, entitled The Shepherd of the Didache, and the First Epistle of Clemens, and the Epistle of Barnabas, and the Apocalypse of Peter.” And on page 5 it says: “The Epistle to the Hebrews and the Apocalypse were the subject of the most intense disputes (between the churches), and the authenticity of their attribution to the apostles (disciples of Christ) was strongly denied for a long time. In the West, the authenticity of the Epistle to the Hebrews was denied, and in the East, the authenticity of the Apocalypse. On the other hand, the Second and Third Epistle of John, the Second Epistle of Peter, and the Epistle of Jude were only slowly accepted.” See also: http://jeromekahn123.tripod.com/newtestament/id10.html “And the concern for unity in the Church, which increased day by day in recognition of the primacy of the Roman authority, contributed in no small way to the alleviation of the differences that arose at one stage or another of the development that accompanied the composition of the canon.” (New Testament Book) The Church History 101 website says that before the second century there was no citation or quotation from what we know today as the New Testament: “

It is not only when we come to the second century apologists that verified citations from what we now call NT texts begin to be common.”

From the above, the following facts can be concluded:- The early Christians did not have a holy book other than the book of the Jews (currently the Old Testament).

- Evidence began to appear that the four Gospels were read in churches after 150 AD and were attributed to the disciples of Christ.

- These works were not considered sacred texts before that time.

- The name of the New Testament did not appear until the end of the second century.

- Works were cited as sacred that were not.

- There were severe disputes between the churches in rejecting and accepting some books (the dispute still exists) .

- There is doubt about the identity of the editors of the Gospels, they may have been the disciples or people related to them.

- The Roman authority reduced the intensity of the disputes, which means supporting a doctrine by force.

But what is the origin of the New Testament? Under the title “The Text of the New Testament” I quote to the reader from the introduction to the Ecumenical Translation, p. 6:

“The text of the twenty-seven books has reached us in a large number of manuscripts written in many different languages, and now preserved in libraries throughout the world. Not one of these manuscripts is written by the author himself, but they are all copies or copies of the books written by the author himself and dictated by him. All the books of the New Testament, without exception, were written in Greek, and there are more than five thousand books written in this language, the oldest of which were written on papyrus and the rest on parchment. We have only fragments of the New Testament on papyrus, some of which are small. The oldest manuscripts that contain most of the New Testament or its complete text are two sacred books on parchment dating back to the fourth century. The most important of them is the Vatican Codex, so called because it is preserved in the Vatican Library. This manuscript is of unknown origin and has unfortunately suffered damage, but it contains the New Testament, except for the Epistle to the Hebrews.” 9/14 - 13/25 and the first and second letters to Timothy and the letter to Titus and the letter to Philemon and Revelation. And the entire New Testament in the book The manuscript called the Sinaiticus, because it was found in the monastery of St. Catherine, and the Epistle to Barnabas and part of the Shepherd of Hermas were added to the New Testament, two works that will not be preserved in the New Testament canon in its final form. The Sinaiticus is preserved today in the British Museum in London. These two volumes were written in a beautiful hand called the large biblical script, and they are the most famous among about 250 written on parchment in the same hand or in a hand that is more or less similar to it, and they date back to a period extending from the third to the tenth or eleventh century, and most of them, and especially the oldest of them, preserve only a very small part sometimes of the New Testament. The copies of the New Testament that have come down to us are not all the same. Rather, differences of varying importance can be seen in them, but their number is very great in any case. There is a group of differences that deal only with some rules of grammar and syntax or words or the arrangement of words, but there are other differences between the manuscripts that deal with the meaning of entire paragraphs. It is not difficult to discover the source of these differences, for the text of the New Testament was copied and copied over many centuries by scribes of varying skill. None of them is immune from the various errors that prevent any copy, no matter how much effort is put into it, from being in complete agreement with the example from which it was taken. In addition, some scribes sometimes tried in good faith to correct what was in their example and it seemed to them to contain clear errors or lack of precision in theological expression. Thus they introduced new readings (phrases) into the text, almost all of which were wrong. Then it can be added that the use of many passages from the New Testament during the performance of the rituals of worship often led to the introduction of embellishments aimed at beautifying the ritual or reconciling different texts, which was facilitated by reading aloud.

It is clear that the changes introduced by scribes over the centuries accumulated one upon the other, so that the text that finally reached the age of printing was burdened with various types of changes that appeared in a large number of readings. The ideal that textual criticism aims for is to scrutinize these different documents in order to establish a text that is as close as possible to the original. In no case can we hope to reach the original text itself.

Through this information, which is the words of Christian scholars concerned with their Holy Book , we can rearrange it into several very important points:

- Although there are many manuscripts of the New Testament, they are not in the handwriting of the author himself, but rather a copy or a copy of a copy. In other words, if we find a manuscript of one of the letters of Peter the Apostle, it is not in Peter’s handwriting, but rather a copy of it.

- The manuscripts of the New Testament were mostly written in Greek, and there are also Coptic, Syriac, and Latin manuscripts, noting that the language of Jesus Christ is not Greek, but Aramaic.

_ Most of these manuscripts contain only a few lines from a chapter of the New Testament (see)

http://www-user.uni-bremen.de/~wie/t...pyri-list.html

_ The oldest Greek manuscripts containing most of the books of the New Testament date back to the fourth century AD

_ There are very many differences between these manuscripts, which may be simple spelling and grammatical errors, but there are errors that cover entire paragraphs.

_Some scribes have sometimes tried in good faith to correct what they found in their example and which seemed to them to contain obvious errors or lack of theological precision. Thus they have introduced into the text new readings (phrases) which are almost entirely wrong.

Origen (a theologian of the third century) condemned the bold alteration of sacred texts by some Christians, and Jerome () informed Pope Damasus of the numerous errors which had appeared in the texts during the attempt at harmonization. Tischendorf, the discoverer of the Sinaiticus, admitted that there were changes in the texts by at least three scribes, and that the present Bible cannot be an exact copy of the original.

The 3rd century Christian writer Origen condemned such Christians for “their depraved audacity” in changing the text. Jerome told Pope Damascus of the "numerous errors" that had arisen in the texts through attempted harmonizing. In 1707 John Mill of Oxford listed 30,000 variants in the different NT texts and at the beginning of this century with further discoveries of manuscripts, the scholar Herman von Soden listed some 45,000 variants in the NT texts illustrating how they were altered. Even in the one fourth century Codex Sinaiticus containing all the NT, Professor Tishendorf, the discoverer, noted that it had been altered by at least three different scripts. Therefore this shows the present-day Bible is not an "inerrant copy" of the original writings.

http://www.golivewire.com/forums/peer-otanib-support-a.html

_ The manuscripts reached the age of printing burdened with various errors.

_ The science of textual criticism means trying to reach the original as much as possible, but it is impossible to reach the original text in any way.

_ Some of the Gospel writers wrote their writings in defense of their theological doctrine. See

On examination of passages arising in the four Gospels, it can be seen that the narrative is composed to suit the theological viewpoint of the evangelist . When comparing a narrative with its parallel in another Gospel, or when a narrative only appears in one Gospel, it becomes obvious that the evangelists had their own beliefs and attitudes, and these sometimes become obvious. It is clear that the authors of the Gospels shaped, molded, selected and adapted the material available to them to suit their purpose

But what are the manuscripts on which the New Testament is based today?

There are two types of manuscripts of the Bible :

the majority texts, the common text, or the received text.

Majority Text -Textus Receptus

It is a Greek text, editions of which were printed between 1514 and 1641. It is based on Greek manuscripts. It is also supported by newly discovered manuscripts. Minority texts: or the Alexandrian text

Minority Text _Alexandrian Text

It is based on only two manuscripts, the Vatican Codex and the Sinaiticus Codex, which contradict not only the texts of the majority, but also contradict each other.

http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/nt_manuscripts.html

There is a dispute between the publishing houses of the Bible as to whether the book is based on the majority or minority manuscripts, and each has its own arguments and evidence. We will first discuss the majority texts:

Majority Texts and Textus Receptus

The Greek text of this type of Bible was made by Erasmus, a Dutch theologian, in 1516 and printed by Desiderius Erasmus

. Erasmus based his edition on six manuscripts from the twelfth century and later, which lacked six phrases that were not present in any of these manuscripts (from the Revelation of John), so he translated them from the Valget Latin version that was widespread at that time. He also used phrases taken from the citations of the early Church Fathers in addition to the Valget version. Erasmus first made corrections to the manuscripts on which he based his first edition, and traces of his corrections are still present. He found it difficult to know the text from the comments in some of these manuscripts, and the result was a text that has no equivalent in any other Greek manuscript. The theologian Daniel Wallace counted 1838 differences between Erasmus's text and the Byzantine text of Hodges and Farstad.

If the "Majority Text" of Hodges and Farstad is taken to be the standard for the Byzantine text-type, then the Textus Receptus differs from this in 1,838 Greek readings, of which 1,005 represent "translatable" differences[1]

The Text of the Textus Receptus

Erasmus, having little time to prepare his edition, could only examine manuscripts which came to hand. His haste was so great, in fact, that he did not even write new copies for the printer; Rather, he took existing manuscripts, corrected them, and submitted those to the printer. (Erasmus's corrections are still visible in the manuscript 2.)

Nor were the manuscripts which came to hand particularly valuable. For his basic text he chose 2e, 2ap, and 1r. In addition, he was able to consult 1eap, 4ap, and 7p. Of these, only 1eap had a text independent of the Byzantine tradition -- and Erasmus used it relatively little due to the supposed "corruption" of its text. Erasmus also consulted the Vulgate, but only from a few late manuscripts.

Even those who favor the Byzantine text cannot be overly impressed with Erasmus's choice of manuscripts; They are all rather late

Translation:

Erasmus did not have time to prepare his editions, he only examined the manuscripts that came to him. His haste was great, in fact he did not write new copies to go to the press but took the manuscripts he had, corrected them, and sent them to the press. (Erasmus' corrections are still noticeable in the manuscripts.) Even the manuscripts that came to him were not of great value. For the most part his text was taken from (2e), (2ap), and (1r). In addition he took from (1eap), (4ap), and (7p). Of these manuscripts only (1eap) is not in the Byzantine style. All these manuscripts date back to after the 12th century AD.

See the website:

http://www.skypoint.com/members/waltzmn/TR.html.

Erasmus issued another edition in 1519 to avoid the mistakes of the first edition, which he rushed to issue to precede another edition that was about to be issued in Spain. Martin Luther used it in his translation of the German version of the Bible. In the third edition, 1522, he added 1 John 5:7, as it supports the doctrine of the Trinity and was present in the Spanish version.

Erasmus added it not because it was in the original ancient Greek manuscripts, but because of pressures exerted on him. See the website:

http://www.bible-researcher.com/bib-e.html

Reprints and editions: Erasmus' first edition (1516) has recently been reprinted in a photographic facsimile: Erasmus von Rotterdam: Novum Instrumentum, Basel 1516: Faximile - Neutral history, text and bibliographischen Einleitung von Heinz Holeczek (Stuttgart and Bad Canstatt: Frommann and Holzboog, 1986). His second edition (1519) differed from the first chiefly in the correction of numerous errors of the press, and in the addition of more notes. In his third edition (1522) Erasmus inserted the so-called Comma Johanneum in 1 John 5:7, not because he believed it to be authentic, but in order to “take away the handle for calumniating him which had been afforded by him honestly following his MSS in this passage ” (Tregelles, Account of the Printed Text, p. 26.

So, the process of selecting the texts to be included in the Bible for printing was interspersed with pressure and negotiations. Then he issued the fourth in 1527 after improving the printing and making some amendments and adding the Vulgate text in an additional column, but he removed it in the fifth edition in 1535 and died a year later. Several editions of the Bible were issued based on this edition, such as:

Stephanus and Beza, Elzevir, and the King James Version (1611). The contemporary theologian Bruce Metzger considered the manuscripts used by Erasmus to be of low value, as he said:

That edition was based mostly upon two inferior twelfth century Greek manuscripts, which were the only manuscripts available to Erasmus “on the spur of the moment” (ibid., page 99).

www.BibleTexts.com/KJV-tr.htm

Thus we see that the versions based on this type of texts (the majority texts) or the common text have many problems such as: Textus Receptus

_ This type of texts is based on only six manuscripts belonging to the twelfth century, contrary to what is rumored that it is based on thousands of manuscripts, as these manuscripts do not match each other. Figure 2 shows the number and names of the manuscripts that Erasmus used in his versions.

_ Erasmus made many corrections himself to the manuscripts, the effect of which is still present.

_ The differences between this text and the Byzantine text are in the hundreds.

_ Erasmus yielded to external pressures and added the text of the First Epistle of John supporting the Trinity. He commented on this text with doubts about its canonicality

most modern scholars consider his text to be of dubious quality

With the third edition of Erasmus' Greek text (1522) the Comma Johanneum was included, because " Erasmus chose to avoid any occasion for slander rather than persisting in philological accuracy ", even though he remained "convinced that it did not belong to the original text of John. "[8] Popular demand for Greek New Testaments led to a flurry of further authorized and unauthorized editions in the early sixteenth century, Almost all of which were based on Erasmus's work and incorporated his particular readings, although typically also making a number of minor changes of their own

With the third edition of Erasmus' Greek text (1522) the Comma Johanneum was included, because " Erasmus chose to avoid any occasion for slander rather than persisting in philological accuracy ", even though he remained "convinced that it did not belong to the original text of John. "[8] Popular demand for Greek New Testaments led to a flurry of further authorized and unauthorized editions in the early sixteenth century, Almost all of which were based on Erasmus's work and incorporated his particular readings, although typically also making a number of minor changes of their own

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textus_Receptus

_ The terms "Majority Texts (Byzantine Text) and Common Text" have always been treated as one and the same, but when Hodges and Farstad produced an edition based on the Byzantine Majority Texts, the result was a text that differed from the Common Text in over a thousand places, see next page.

When the text was being compiled by the majority Hodges and Farstad, their collaborator Pickering estimated that their resulting text would differ from the textus receptus in over 1,000 places; In fact, the differences amounted to 1,838. In other words, the reading of the majority of Greek manuscripts differs from the textus receptus (Hodges and Farstad used an 1825 Oxford reprint of Stephanus' 1550 text for comparison purposes) in 1,838 places, and in many of these places, the text of Westcott and Hort agrees with the majority of manuscripts against the textus reception. The majority of manuscripts and Westcott and Hort agree against the textus receptus in excluding Luke 17:36; Acts 8:37; and I John 5:7 from the New Testament, as well as concurring in numerous other readings (such as “tree of life” in Revelation 22:19). Except in a few rare cases, writers well-versed in textual criticism have abandoned the textus receptus as a standard text

_ It is accepted that the common text issued by Erasmus was modified several times not only by its first author but also by those who came after him such as Stephanus and Beza

_ The text resulting from Erasmus's editions does not match any manuscript exactly because it is a synthetic text whose author composed between six manuscripts and made use of the Vulgate, so no edition of the Bible can matchany complete manuscript, because there are no two identical Greek manuscripts:

There is no Greek manuscript that agrees exactly with either of these. Both of them are conflate texts

http://www.biblicist.org/bible/receptus.shtml

__The King James Version and the Common Text of Erasmus are said to be based on over five thousand manuscripts but for example the famous Trinitarian phrase 1 John 5:7 which Erasmus added in his third edition and which is in the King James Version is found in only four of the five thousand manuscripts in question.

the King James Version does not exactly follow the majority of Greek NT manuscripts. For instance, 1 John 5:7, found in the KJV and TR, occurs in only four (out of nearly 5000) Greek NT manuscripts . The reading “book of life” in Rev. 22:19 is found in no Greek manuscript.

__ The majority manuscripts and the common text, which belong to the Byzantine type, were all written from the eighth century onwards. As for the Byzantine manuscripts written between the fourth and seventh centuries, they nevertheless belong to the minority texts (we will discuss them later).

Among manuscripts copied before AD 400 (three centuries after the NT was completed) there are none of the Textus Receptus type (Byzantine family), even though we have over seventy manuscripts from this period. From AD 400 to 700, Byzantine manuscripts are still in the minority

http://www.biblicist.org/bible

/receptus.shtml

_ In the second half of the nineteenth century, a new version of the Bible was issued by Wescott & Hort, which differs from the common Byzantine text in many places, because they based their version on another type of manuscripts, the Alexandrian style, the most famous of which are the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, which belong to the fourth century AD. These are the manuscripts that contain the oldest, almost complete texts of the New Testament. The following figure shows the difference between the common Byzantine text and the Alexandrian text. Details of the differences between the two types of text can be reviewed through the site shown in the figure.

Second: Minority Texts or Alexandrian Texts : The Sinaiticus Manuscript: Belongs to the fourth century AD (between 330 and 350 AD).

" You cunning fool, won't you leave the old reading alone and not change it?

The Christian controversy over these manuscripts:

The phrase supporting the Trinity in the First Epistle of John, and they attack strongly the publishing houses that issue modern versions and those behind them from the textual critics, so we see them claiming that the common text is supported by older versions of the Alexandrian manuscripts such as the Old Latin version and the Vulgate version of Jerome and the Peshitta version because they belong to the third century as they say in order to miss the opportunity for those enthusiasts for the Alexandrian texts as the oldest and therefore the best, and since they date back to the fourth century, they are therefore not better than those belonging to the third century, see the following:

| This image is in another size. Click here to view the image in its correct form. The image dimensions are 928x382. |

Second: Minority Texts or Alexandrian Texts : The Sinaiticus Manuscript: Belongs to the fourth century AD (between 330 and 350 AD).

In 1844, the German theologian Constantin von Tischendorf was visiting the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai, Egypt, and saw a group of ancient manuscripts thrown in the monastery's trash can, ready to be used as fuel for the monastery's furnace. Tischendorf was able to keep them and hand them over to the university library in Leipzig, Germany. They then moved to the Russian National Library, where they remained for several decades until the Soviet Union sold them to the British Museum in 1933. There are scholars who doubt the story of their presence in the trash can, but this is not an important issue. Contents of the manuscript: The Old Testament, the New Testament , and also includes the non-canonical chapters of the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas. The Vatican Manuscript: It was discovered by Pope Nicholas V in 1448 as a neglected manuscript in the Vatican, and no one knows exactly where it was written. It may have been Alexandria, Palestine, or southern Italy. It was most likely written in the first half of the fourth century, like the Sinaiticus Manuscript, and it is kept in the Vatican Library. Until the nineteenth century, the Vatican did not allow any Christian scholar to see it until it fell into the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809 and remained in Paris until 1815, then returned to the Vatican Library again. Contents of the manuscript: It contains the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament, but it lacks some parts of the Maccabees and the Prayer of Manasseh, King of Judah, with the loss of some parts of the Book of Genesis and some Psalms. As for the New Testament, it lacks the letters of Paul to Timothy 1 and 2, Titus and Philemon, in addition to the Revelation of John the Theologian. There are traces of corrections by a tenth-century scribe in the manuscript. Also, on page 1512 there is an interesting comment that means:

| This image is in another size. Click here to view the image in its correct form. The image dimensions are 929x340. |

The Christian controversy over these manuscripts:

Comparing modern versions of the Bible with each other, we will find many differences. For example, comparing the King James Version (based on the Byzantine majority manuscripts) and versions such as the International Virgin and Revised Standard Virgin (which are based on the Alexandrian minority texts) the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, there are approximately five thousand differences between the two groups, due to the fourth-century versions that differ from the Byzantine texts.

Most of the over 5000 New Testament differences between the King James Bible and modern Bible versions like the NASB, NIV, RSV, Living Bible, and others, are the result of mainly two manuscripts which allegedly date to around 350 AD called Sinaiticus (Aleph) and Vaticanus (B). http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/vaticanus.html From here we can see the reason for the controversy among Bible publishers about which versions represent the closest thing to the original text, as those who take the Alexandrian manuscripts as their source on the basis that they are the oldest and most complete produce a text that differs from those who take the Byzantine Common Text manuscripts as their source. Compare the King James Version with the modern versions we mentioned before such as (NIV, RSV), and it is noticeable that conservative clerics defend the style

The common text and the Byzantine texts are very enthusiastically used as proofs for all the disputed phrases and paragraphs such as the story of the adulterous woman in the Gospel of John and the end of the second Gospel of Mark and

A vital fact to remember is that though codices Aleph and B (produced in the 4th century) are older than other Greek manuscript copies of the Scriptures, they are not older than the Peshitta, Italic, the Old Latin Vulgate and the Waldensian versions which were Produced 200 years earlier in the 2nd century. All these versions, copies of which are still in existence, agree with Textus Receptus, the underlying text of the King James Bible. I repeat: these ancient versions are some 200 years older than Vaticanus and Sinaiticus: so the 'oldest is best' argument should not be used. .

http://atschool.eduweb.co.uk/sbs777/...v/part1-4.html

http://atschool.eduweb.co.uk/sbs777/...v/part1-4.html

The writer here wants to say that if the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus volumes are the best because they are older than the Greek manuscripts (from which the common or received text was taken), they are not older than the Syriac and Old Latin Peshitta versions.

This statement contains a lot of deception because:

_ To say that it agrees with the King James Version is wrong because there is no complete manuscript that agrees completely with it, as the King James Version is based on the versions of Erasmus, which in turn is a consensual version resulting from the reconciliation of six manuscripts.

http://www.westcotthort.com/dkutilek/whvstr.html

_ Some of them contain non-canonical books (the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas) such as the Sinaiticus manuscript.

- By comparing the Vatican text with other manuscripts, Mr. John William Bergen, a professor at Oxford, found in his book written in 1881 under the name

The Revision Revised

that:

It is worth noting that these differences are not the same in the two manuscripts.

See:

Mr. Burgon states on page 11; "Singular to relate Vaticanus and Aleph have within the last 20 years established a tyrannical ascendance over the imagination of the Critics, which can only be fitly spoken of as a blind superstition. It matters nothing that they are discovered on careful attention to differ essentially, not only from ninety-nine out of a hundred of the whole body of extant MSS. besides, but even from one another. In the gospels alone B (Vaticanus) is found to omit at least 2877 words: to add 536, to substitute, 935; to transpose, 2098: to modify 1132 (in all 7578): - the corresponding figures for Aleph being 3455 omitted, 839 added, 1114 substitued, 2299 transposed, 1265 modified (in all 8972). "Substitutions, transpositions, and modifications, are by no means the same in both. It is in fact easier to find two consecutive verses in which these two mss. differ the one from the other, than two consecutive verses in which they entirely agree." http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/vaticanus.html - The Vaticanus Codex was modified in the tenth or eleventh century, causing some scholars to question the value of a modified manuscript. In the fifteenth century, some parts were added from other manuscripts, causing some scholars to question the value of a manuscript that had been tampered with. See

http://hissheep.org/kjv/the_great_uncials.html

_ The Sinaiticus manuscript was also edited by more than one writer and was amended by others. Tischendorf counted more than 14,800 amendments to the manuscript, most of which were made in the sixth or seventeenth century. See

_ Although the Peshitta, Old Latin and Vulgate versions are older than the Alexandrian versions, we do not have a complete manuscript of these versions written in the second and third centuries in our hands. We do not know exactly the contents of these versions, since modifications to the versions were always a prevailing principle in those eras, and we will mention them shortly. So the commentator’s statement that the versions still exist is answered by asking, what is the date of writing of each of them? You will find them all after the fourth century.

_ The statement that these versions agree with the common text is wrong, and we will prove that when mentioning their dates.

_ The statement that these versions agree with the common text is wrong, and we will prove that when mentioning their dates.

To know that there is no evidence of Byzantine texts before the fourth century, refer to the following figure. It says that the claim of the existence of Byzantine texts before the fourth century is not proven. And that the Syriac fathers Ephraim and Ephratis did not cite phrases from the Peshitta, and therefore they date back to after the fourth century.

On the other hand, the Byzantine text-type, of which the textus receptus is a rough approximation, can boast of being presented in the vast majority of surviving manuscripts, as well as several important versions of the New Testament from the fourth century or later , and as the text is usually found in the quotations of Greek writers in the fifth century and after. The most notable version support for the Byzantine text is in the Peshitta Syriac and the fourth century Gothic version. A second-century date for the Peshitta used to be advocated, but study of the Biblical quotations in the writings of Syrian Fathers Aphraates and Ephraem has demonstrated that neither of these leaders used the Peshitta, and so it must date from after their time, i.e. , to the late fourth century or after. Therefore, this chief support for a claimed second-century date for the Byzantine text-type has been shown to be invalid.

http://www.westcotthort.com/dkutilek/whvstr.html

http://www.westcotthort.com/dkutilek/whvstr.html

So the Byzantine texts, which are the origin of the common text, did not exist before the fourth century. Rather, there are manuscripts belonging to the period between the fifth and eighth centuries, and although they are Byzantine, they agree with the Alexandrian (minority) in terms of the style of the texts, as we explained previously.

On the down side, the distinctively Alexandrian text all but disappears from the manuscripts after the 9th century. On the other hand, the Byzantine manuscripts, though very numerous, did not become the “majority” text until the ninth century, and though outnumbering Alexandrian manuscripts by more than 10:1, are also very much later in time, most being 1,000 years and more removed from the originals.

http://www.westcotthort.com/dkutilek/whvstr.html

Thus we have seen the zealous and conservative adherence of the Christian clergy to the pattern of the common text and we have learned the reason for that, but the scholars of textual criticism in the modern era are of a different opinion as these critics from the various schools of textual criticism no longer defend the texts of the common majority as in this article which says that scholars of textual criticism do not see priority for these texts :

No school of textual scholarship now continues to defend the priority of the Textus Receptus;

http://textus-receptus.com/wiki/Textus_Receptus

http://textus-receptus.com/wiki/Textus_Receptus

As for the texts of the Alexandrian minority, the most important of which are the Vatican and Sinaiticus texts, we summarize their problems as follows:

- They are said to be among the oldest complete copies of the Holy Bible, but the truth is that they lack some parts. For example:

the Vatican manuscript lacks Matthew 3, the first and second letters to Timothy, the letter to Titus, Philemon, some of the Hebrews, and the entirety of Revelation.

- They are said to be among the oldest complete copies of the Holy Bible, but the truth is that they lack some parts. For example:

the Vatican manuscript lacks Matthew 3, the first and second letters to Timothy, the letter to Titus, Philemon, some of the Hebrews, and the entirety of Revelation.

- By comparing the Vatican text with other manuscripts, Mr. John William Bergen, a professor at Oxford, found in his book written in 1881 under the name

The Revision Revised

that:

The Vatican text removes 2,877 words, adds 536 words, replaces 935 words, relocates 2,028 words, and modifies 1,132 words. While the Sinaiticus removes 3,455 words, adds 839 words, replaces 1,114 words, relocates 2,299 words, and modifies 1,265 words, and this is in the Gospels only.

See:

Mr. Burgon states on page 11; "Singular to relate Vaticanus and Aleph have within the last 20 years established a tyrannical ascendance over the imagination of the Critics, which can only be fitly spoken of as a blind superstition. It matters nothing that they are discovered on careful attention to differ essentially, not only from ninety-nine out of a hundred of the whole body of extant MSS. besides, but even from one another. In the gospels alone B (Vaticanus) is found to omit at least 2877 words: to add 536, to substitute, 935; to transpose, 2098: to modify 1132 (in all 7578): - the corresponding figures for Aleph being 3455 omitted, 839 added, 1114 substitued, 2299 transposed, 1265 modified (in all 8972). "Substitutions, transpositions, and modifications, are by no means the same in both. It is in fact easier to find two consecutive verses in which these two mss. differ the one from the other, than two consecutive verses in which they entirely agree." http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/vaticanus.html - The Vaticanus Codex was modified in the tenth or eleventh century, causing some scholars to question the value of a modified manuscript. In the fifteenth century, some parts were added from other manuscripts, causing some scholars to question the value of a manuscript that had been tampered with. See

John Burgon made a personal examination of it and found some major problems with in the manuscript. This has been confirmed by many others. Here are just a few of the problems. "The entire manuscript has had the text modified, every letter has been run over with a pen, making exact identification of many of the characters impossible." (Vaticanus and Sinaiticus - www.waynejackson.freeserve.co.uk/kjv /v2.htm). Dr. W. Eugene Scott, who owns a large collection of ancient Bible manuscripts and Bibles says, “The manuscript is faded in places; scholars think it was overwritten letter by letter in the 10th or 11th century, with accents and breathing [marks] added along With corrections from the 8th, 10th and 15th centuries. All this activity makes paleographic analysis impossible. Missing portions were supplied in the 15th century by copying other Greek manuscripts. (Codex Vaticanus by Dr. W. Eugene Scott, 1996).

I question the "great witness" value of any manuscript has been overwritten, doctored, changed and added to for more than 10 centuries. Let me tell you more.

I question the "great witness" value of any manuscript has been overwritten, doctored, changed and added to for more than 10 centuries. Let me tell you more.

http://hissheep.org/kjv/the_great_uncials.html

_ The Sinaiticus manuscript was also edited by more than one writer and was amended by others. Tischendorf counted more than 14,800 amendments to the manuscript, most of which were made in the sixth or seventeenth century. See

Tischendorf said that he "counted 14,800 alterations and corrections in Sinaiticus

http://www.sermonaudio.com/comments_view.asp?onlyname=true&keyword=Bibleworm

http://www.sermonaudio.com/comments_view.asp?onlyname=true&keyword=Bibleworm

_ The Sinaiticus manuscript was written with obvious negligence, as entire phrases were repeated or a phrase was started and then deleted, as John Bergen says.

A great amount of carelessness is exhibited in the copying and correction. 'Codex Sinaiticus 'abounds with errors of the eye and pen to an extent not indeed unparalleled, but happily rather unusual in documents of first-rate importance.' On many occasions 10, 20, 30, 40 words are dropped through very carelessness . Letters and words, even whole sentences, are frequently written twice over, or begun and immediately canceled; while that gross blunder, where by a clause is omitted because it happens to end in the same words as the preceding clause, occurring no less than 115 times in the New Testament. (John Burgon, The Revision Revised )It is clear that the scribes who copied the Codex Sinaiticus were not faithful men of God who treated the Scriptures with utmost reverence. The total number of words omitted in the Sinaiticus in the Gospels alone is 3,455 compared with the Greek Received Text (Burgon, p. 75)

http://www.1611kingjamesbible.com/codex_sinaiticus.html/

_ This is in addition to the fact that the two manuscripts differ from each other in the Gospels more than three thousand times.

_ This is in addition to the fact that the two manuscripts differ from each other in the Gospels more than three thousand times.

The oldest manuscripts (the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus) are not reliable at all! But wait, the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus disagreed with each other over 3,000 times in the gospels alone

http://www.chick.com/information/bib...jamesbible.asp

It is said to have been written in Antioch, the capital of Syria at the time, around 150 AD, making it older than the Alexandrian texts. But is there a manuscript of the Peshitta dating back to this date? In fact, the oldest copy of the Peshitta dates back to the fifth century. Of the approximately one hundred manuscripts of the Peshitta in the British Library, 60 date from the first millennium and 30 from the fifth to the seventh century.

The two oldest manuscripts in Old Syriac date back to the late fourth or early fifth century:

http://www.chick.com/information/bib...jamesbible.asp

Thus we know that the Alexandrian minority manuscripts are rejected by a large segment of Christians, although they are considered the reliable source for modern versions of the Bible. As is clear, the dispute is still raging among Christians concerned with the Bible, from critics and clergymen, about which type of manuscripts to rely on in an attempt to return to the original text as much as possible.

The problem is that those who are enthusiastic about the majority texts and the common text face the criticism that their many manuscripts not only do not match each other but also belong to the ninth century and later. And since they defend their choice by saying that if the choice of critics is the Alexandrian texts, claiming that they are the most complete and oldest versions, which means that they are superior, then there are older versions of Alexandria that support the common text type, such as the Syriac Peshitta and Old Latin.

And northern Italy. Okay, let's see the history of these versions.The problem is that those who are enthusiastic about the majority texts and the common text face the criticism that their many manuscripts not only do not match each other but also belong to the ninth century and later. And since they defend their choice by saying that if the choice of critics is the Alexandrian texts, claiming that they are the most complete and oldest versions, which means that they are superior, then there are older versions of Alexandria that support the common text type, such as the Syriac Peshitta and Old Latin.

Syriac Peshitta:

The two oldest manuscripts in Old Syriac date back to the late fourth or early fifth century:

There are two fifth-century manuscripts of the Old Syriac separate gospels (the Sinaitic Palimpsest and Curetonian Gospels

http://www.masters-table.org/forinfo/peshitta.htm

http://www.masters-table.org/forinfo/peshitta.htm

First:

The Sinaitic Palimpsest

was discovered in the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. It consists of 358 pages and dates back to the end of the fourth century. It contains the four Gospels in Syriac, which were corrected by some of the saints in the monastery in 778 AD. This manuscript is the oldest Syriac translation of the four Gospels.

The Sinaitic Palimpsest

was discovered in the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. It consists of 358 pages and dates back to the end of the fourth century. It contains the four Gospels in Syriac, which were corrected by some of the saints in the monastery in 778 AD. This manuscript is the oldest Syriac translation of the four Gospels.

The Syriac Sinaitic (syrs), also known as the Sinaitic Palimpsest , of Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai is a late 4th century manuscript of 358 pages, containing a translation of the four canonical gospels of the New Testament into Syriac , which have been overwritten by a vita (biography) of female saints and martyrs with a date corresponding to AD 778. This palimpsest is the oldest copy of the gospels in Syriac, one of two surviving manuscripts (the other being the Curetonian Gospels ) that possibly predate the Peshitta (although this is debated), the standard Syriac translation of the Bible.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syriac_Sinaiticus

The Curetonian Gospels , designated by the siglum syrcur, are contained in a manuscript of the four gospels of the New Testament in Old Syriac , a translation from the Aramaic originals, according to William Cureton [1] [2] The order of the gospels is Matthew, Mark, John, Luke differing significantly from the canonical Greek texts, with which they had been collated and "corrected"; Henry Harmon concluded, however, that their originals had been Greek from the outside.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syriac_Sinaiticus

Second:

Curetonian Gospels

: A manuscript containing the four Gospels in Old Syriac. It is a translation of an Aramaic original (according to William Cureton, an English orientalist from the 19th century), but it differs from the canonical Greek Gospels that were collected and corrected. The order of the Gospels in this manuscript is: Matthew - Mark - John - Luke.

Curetonian Gospels

: A manuscript containing the four Gospels in Old Syriac. It is a translation of an Aramaic original (according to William Cureton, an English orientalist from the 19th century), but it differs from the canonical Greek Gospels that were collected and corrected. The order of the Gospels in this manuscript is: Matthew - Mark - John - Luke.

The Curetonian Gospels , designated by the siglum syrcur, are contained in a manuscript of the four gospels of the New Testament in Old Syriac , a translation from the Aramaic originals, according to William Cureton [1] [2] The order of the gospels is Matthew, Mark, John, Luke differing significantly from the canonical Greek texts, with which they had been collated and "corrected"; Henry Harmon concluded, however, that their originals had been Greek from the outside.

So, the claim that there are Syriac manuscripts from the second century is incorrect :

The most notable version support for the Byzantine text is in the Peshitta Syriac and the fourth century Gothic version. A second-century date for the Peshitta used to be advocated, but study of the Biblical quotations in the writings of Syrian Fathers Aphraates and Ephraem has demonstrated that neither of these leaders used the Peshitta, and so it must date from after their time, i.e. , to the late fourth century or after. Therefore, this chief support for a claimed second-century date for the Byzantine text-type has been shown to be invalid

A study of the quotations of the Syrian Fathers Aphraates and Ephraim showed that they did not use the Peshitta in any quotation, so its date is closer to the end of the fourth century.

http://www.bible-researcher.com/kutilek1.html

Some information about the Peshitta:

It was later used in the Gospel section.

http://www.bible-researcher.com/kutilek1.html

Some information about the Peshitta:

The Peshitta has been considered the holy book of the Syriac churches since the fifth century AD, although it existed before that, perhaps from the second century (there are no manuscripts), but with a different name . Old Syriac Bible or Vetus Syra under the name of the Old Syriac Text.

_ Some Greek canonical books such as 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation of John the Theologian are not included.

_ The Diatessaron was used instead of the four Gospels, which is a combination of the four Gospels prepared by Tatian to avoid repetition. This Tatian was an Assyrian theologian from the second century.

Tatian the Assyrian was an early Christian writer and theologian of the second century .

Tatian's claim to fame is the Diatessaron , a harmony of the four gospels that became the standard text of the four gospels in the Syriac-speaking ******es until the 5th-century, when it gave way to the four separate gospels in the Peshitta version.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tatian

Tatian's claim to fame is the Diatessaron , a harmony of the four gospels that became the standard text of the four gospels in the Syriac-speaking ******es until the 5th-century, when it gave way to the four separate gospels in the Peshitta version.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tatian

_ It is worth noting that Tatian's text is closer to the system of the Gospel of Luke, and it was gradually modified to fit the Latin Vulgate version. See:

_ In the 7th century AD a Syriac version was produced based on the Greek text.

With the gradual adoption of the Vulgate as the liturgical Gospel text of the Latin ******, the Latin Diatessaron was increasingly modified to conform to Vulgate readings. In 546 Victor of Capua discovered such a mixed manuscript; and, further corrected by Victor so as to provide a very pure Vulgate text within a modified Diatessaron sequence, this harmony, the Codex Fuldensis , survives in the monastic library at Fulda

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diatessaron

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diatessaron

The Syriac churches that used the Diatessaron were pressured to replace it with the four canonical Gospels like the rest of the churches. See

However, the Syriac-speaking ****** was urged to follow the practice of other ******es and use the four separate gospels. Theodoret , bishop of Cyrrhus on the Euphrates in upper Syria in 423, sought out and found more than two hundred copies of the Diatessaron, which he 'collected and put away, and introduced instead of them the Gospels of the four evangelists'. http://peshitta.co.tv

_ In the 7th century AD a Syriac version was produced based on the Greek text.

In the seventh century , a complete Syriac Bible based on the standard Greek was produced

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peshitta

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peshitta

This is because the Diatessaron was not considered legal by many Christians. See:

_ The fifth century manuscripts of the Peshitta did not include the story of the adulterous woman, see

The Diatessaron was so corrupted that in later years a bishop of Syria threw out 200 copies, since ****** members were mistaking it for the true Gospel.

http://www.biblebelievers.net/biblev...s/kjcforv4.htm

http://www.biblebelievers.net/biblev...s/kjcforv4.htm

_ The fifth century manuscripts of the Peshitta did not include the story of the adulterous woman, see

The Peshitta does not contain four of the General Epistles (2 Keepa, 2 Yukhanan, 3 Yukhanan and Yehuda), the book of Revelation, nor the story of the woman taken in adultery (Yukhanan 8.) These writings are not considered canonical by the ****** of the East, and have never been included in the Canon of the Peshitta. The script used will be the original Estrangela, without vowel markings that were introduced during the 5th century

The Peshitta does not contain the 4 general epistles, the Apocalypse, and the story of the adulterous woman.

http://www.peshitta.org/initial/peshitta.html

_ In the seventh century a copy was produced in the style of the Greek text.

It is the Latin version of the Bible dating back to the beginning of the fifth century AD, written by Jerome as commissioned by Pope Damasus I in the late fourth century AD. The Old Testament in it was translated from the Hebrew version (Tanakh) and not the Greek Septuagint. It was considered the official version of the Roman Catholic Church until the year 1500 and contains three apocryphal books: the Song of the Three Children, the Story of Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon . It is worth noting that the Vulgate version was not produced by Jerome alone, but there are unknown people who contributed to it . See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgate

http://www.peshitta.org/initial/peshitta.html

Now we remind the reader of the problems of the Beshita and summarize them as follows:

There are no manuscripts of it older than the fifth century, and we do not know what the Syriac copies of the Bible were like in the second century and what their contents were.

_ The four canonical Gospels were replaced by the non-canonical Diatessaron.

_ It lacks four general messages, the vision, and some places such as the story of the adulterous woman.

_ The four canonical gospels were brought back again under pressure from the rest of the churches.

This means that many changes were made to the Peshitta text more than once.

Valgit version:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgate

The Vulgate has a compound text that is not entirely the work of Jerome. [2] Its components include:

Polycarp and the Epistle to the Galatians:

Note here that Father Polycarp, as usual, often quotes part of the phrase, not all of it, and this part may not match its equivalent in the Bible:

Galatians 4:26:

Galatians 4:26: But the Jerusalem above is free, and she is our mother.

Polycarp said:

“And she is the mother of us all.”

Is this quote suitable to replace the original? Can the phrase be reconstructed from it? I think if we tried, the result would be a completely different Bible.

Galatians 6:7: Do not be deceived, for God is not mocked, but a man reaps what he sows.

Polycarp said :

“The Lord is not mocked.”

Galatians 1:1: From Paul, an apostle, not by men nor by the will of man, but by the will of Jesus Christ and of God the Father, who raised him from the dead.

Polycarp said:

“His Father who raised him from the dead.”

From 1 Thessalonians:

5:7 : For those who sleep sleep at night, and those who get drunk get drunk at night.

Ignatius said:

“Continue praying.”

People! Is this a good quote?

From the Epistle to the Colossians:

Colossians 1:23 : If you continue in the faith, grounded and steadfast and are not moved away from the hope of the gospel which you heard, which was preached to every creature under heaven, of which I, Paul, became a minister,

Ignatius mentioned:

“Continue in the faith.”

For those who want more, see:

http://www.ntcanon.org/Ignatius.shtml

I think it is clear that the two caveats are real, either the phrase used is too short, or it lacks accuracy, and I add to that that these citations are absolutely not suitable for reconstructing the Holy Bible

. _____

As for oral transmission, it is known that no Christian memorizes the Holy Bible by heart like the Holy Quran, especially since there was no such thing as the New Testament before the year 150 AD, and it began to develop over a long period of time, adding books and then removing them again. So how can oral memorization be achieved in this situation? Here is a diagram showing the break in the chain of transmission: Christianity was affected by politics:

Christianity was a persecuted religion in the first three centuries, and the church did not breathe a sigh of relief until Emperor Constantine decided to embrace it. This had a great impact on religion and the world as it became the religion of the Roman Empire. The Bibleufo.com website says that Christianity

was a victim of the Roman Empire under the rule of Constantine, who merged Christianity with Roman pagan practices and removed it from the influence of the Jewish religion and the early Christian church. After he had established his authority and tightened his control over the western part of the empire in 312, he issued the Edict of Religious Freedom

, known as the Edict of Milan ,

which made Christianity equal to the pagan religion of Rome and was no longer persecuted. Constantine relied on the support of the church for his rule in exchange for his protection of it. There was an alliance between the two parties, asHe got rid of hundreds of books that did not agree with the church doctrine and combined the doctrines and worship of Christianity with some practices of the pagan religion of Rome. In the year 330, he began to attack paganism in a clever way in order to convince the public to follow the laws through this combination. For example, he made December 25, the birthday of the pagan god "the sun", the official birthday of Christ. He also replaced Saturday with Sunday and considered everything related to the Jewish religion reprehensible. After the First Ecumenical Council, he got rid of books that were previously considered sacred but did not fit the doctrine of the Council.

See the following page:

http://www.bibleufo.com/anomlostbooks.htm

Here, dear reader, are some of the names of the lost books mentioned in the Bible:

The Book of Samuel the Prophet

The Book of Nathan the Prophet

The Book of Gad the Prophet

1 Chronicles 29-29 : Now the acts of King David, first and last, are written in the book of the chronicles of Samuel the seer, and the

Nathan the prophet, and the chronicles of Gad the seer The history of the prophet Iddo 2 Chronicles 13-22: And the rest of the acts of Abijah , his ways, and his sayings, are written in the book of ... Examples: 1 - The story of the adulterous woman: in John 8_11:3 This passage is called by Christian manuscript scholars ( Pericope Adulterae ) and is not found in many versions of the Bible because it is not found in the oldest Greek manuscripts, so the controversy over it still exists between supporters of the Alexandrian text and supporters of the common text who include it in their gospels and defend it. The website: http://www.bsw.org/project/biblica/bibl80/Ani01.htm says that there is agreement among many manuscript scholars that this story is not originally part of the Gospel of John, as it is not found in the oldest manuscripts, and if it is found, it is sometimes in its known location John 7:57 or in other places such as John 8:36 or John 8:44 or Luke 21:38. The theologian

See the previous site. The strange thing is that despite her being caught red-handed doing the same thing, we never heard of her partner in the crime and he was supposed to be stoned as well. Then what is meant by the one who is without sin? Is it the sin of adultery or any sin? If it is the sin of adultery, it is unreasonable for everyone to be an adulterer, and even if they were, the natural reaction would be to pick up stones to claim their innocence. But if it is any sin, then who among the people is without any sin? And then no sinner can be punished???

As he says under the heading: “Marginal Comments in Various Versions”:

“Most ancient (religious) authorities omit the story”

American Standard Bible 1901

“Most authorities omit it or give a different text or place it in Luke 21:38”

ASB 1946

“Not found in most ancient manuscripts”

New American Standard Bible 1963

“Not found in reliable manuscripts”

New International Version 1973

And this is not limited to:

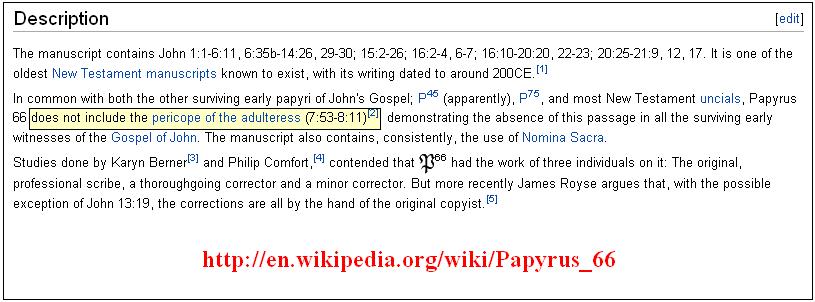

This story is not found in it . As for the oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of John, which are almost complete and are called (P66), the manuscript (P75) also does not contain the story and is a witness from the third century to the Gospel of John. In fact, the oldest manuscript that contains the story is the Codex Bezae manuscript from the century. Bruce Metziger's speculations seem reasonable that the story was known in the Western Church more. Papias (second century) said that there is a story of a woman with many sins who were brought to Christ in the Gospel of the Hebrews (non-canonical) and she may be the same woman. However, there are references in writings from the third century (Didascalia) and the fourth (Dydymus the Blind) that refer to the story. Jerome mentioned that the manuscripts of the Latin West in the late fourth century contained the story. Some of the Latin Fathers (Ambrose and Augustine) mentioned that the story seems to have been removed from many manuscripts so that it would not appear that Christ approves of adultery or tolerates it. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pericope_Adulter%C3%A6 Another witness against the story is its absence in the Beshita, see:

http://www.peshitta.org/initial/peshitta.html

Accordingly, the Diatessaron does not bear witness to the story either:

English scholar Samuel Tregillis comments on the story in an article he wrote in London in 1854, saying: “I am quite sure that the story is not from the original text of the Gospel of John.” He ends his speech, however, saying that the story seems to be true but is not part of the Holy Revelation, and this is almost the same opinion as Bruce Metziger. See the text of Samuel Tregillis’s speech:

http://www.bible-researcher.com/adult.html See Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Stuttgart, 1971), pages 219-221. There are those who argue that the story is mentioned in some other ancient writings, such as a collection of books that the public believes to be the writings of the apostles, such as the Apostolic Constitution.

A fourth-century pseudo-Apostolic collection , in eight books, of independent, though closely related, treatises on Christian discipline , worship, and doctrine , intended to serve as a manual of guidance for the clergy , and to some extent for the laity .

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01636a.htm

- Jerome's independent translation from the Hebrew : the books of the Hebrew Bible, usually not including his translation of the Psalms . This was completed in 405.

- Translation from the Greek of Theodotion by Jerome: The three additions to the Book of Daniel ; Song of the Three Children , Story of Susanna , and The Idol Bel and the Dragon . The Song of the Three Children was retained within the narrative of Daniel, the other two additions Jerome moved to the end of the book.

- Translation from the Septuagint by Jerome: the Rest of Esther . Jerome gathered all these additions together at the end of the book of Esther.

- Translation from the Hexaplar Septuagint by Jerome: his Gallican version of the Book of Psalms. Jerome's Hexaplaric revisions of other books of Old Testament continued to circulate in Italy for several centuries, but only Job and fragments of other books survive.

- Free translation by Jerome from a secondary Aramaic version: Tobias and Judith .

- Revision by Jerome of the Old Latin , corrected with reference to the oldest Greek manuscripts available: the Gospels .

- Old Latin , more or less revised by a person or persons unknown: Baruch , Letter of Jeremiah , 3 Esdras , [3] Acts , Epistles , and the Apocalypse .

- Old Latin , wholly unrevised: Epistle to the Laodiceans , Prayer of Manasses , 4 Esdras , Wisdom , Ecclesiasticus , and 1 and 2 Maccabees .

Thomas Lecker, an Oxford professor and physician to King Henry VII and VIII, commented that when he read the Greek Gospels and compared them with the Latin Vulgate, he said: “ Either the Greek Gospels are not Gospels or we are not Christians .” See

The reason for the disagreement is that the Vulgate was translated based on the Vatican text manuscript, which differs from the common text in many places. See

http://www.biblestudy.org/basicart/does-it-matter-which-bible-is-used-for-bible-study.html

Before the Latin Vulgate there was the Old

Latin Vetus Latina or Italic.

There is no single complete copy of this Old Latin text, but there are some manuscripts that contain parts of this text that preceded Jerome's text. Bruce Metziger, an American theologian, compared a manuscript containing Luke 24:4-5 and found no fewer than twenty-seven differences. See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vetus_Latina

See

http://www.bible-researcher.com/kutilek1.html

The article says that Catholic clergy in Britain are warning their followers that they should not expect complete accuracy from the Bible, whether scientific or historical, and that some parts of the book are incorrect. End of the Times.

Quotations and quotations from the early church fathers from the New Testament

Can the Bible really be compiled from the testimonies and quotations of the fathers, as they claim?

The introduction to the French ecumenical translation of the New Testament, 12th edition, Beirut, p. 8, states

: “However, these testimonies have two drawbacks. Not only does each of them only quote a small part of the text , but the fathers, unfortunately for us, often quoted it from memory and without paying much attention to accuracy. In this case, we cannot fully trust what they transmit to us .” There is no doubt that this statement is correct, and we will prove it, God willing. Here are examples of the writings of the early fathers of the church, and we will compare them with what is available now in modern editions: Father Polycarp: A Christian bishop (69-155 AD) in the ancient Greek city of Smyrna (currently Izmir) and is considered a saint by all Christian sects. Here is an example of Polycarp's citation of the Gospel of Matthew http://www.ntcanon.org/Polycarp.shtml Comparing what Polycarp wrote with Matthew 7, verses 1 and 2: Download images _ Do not judge, lest you be judged . For with what judgment you judge, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you. Polycarp added, "And forgive, that you may be forgiven ." Comparing what Polycarp said with Matthew 6, verse 13:13 _ And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, for thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, forever. Amen. Polycarp limited himself to "And lead us not into temptation." Matthew 26, verse 41:41 _ _ Watch and pray that you may not enter into temptation, for the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak . Polycarp only mentioned the second half, " For the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak ." Matthew 5:44: 5- But I say to you, Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who despitefully use you and hate you. Polycarp mentioned: “For those who persecute and hate you .” Polycarp and the Gospel of Mark: Polycarp mentioned the phrase (A servant of all) “a servant of all” which he quoted from Mark 9:35 while Mark 9:35 is as follows: And he sat down and called the twelve and said to them, “Whoever wants to be first of all must be last of all and servant of all.” Polycarp and the Acts of the Apostles: Polycarp stated: “Whom the Lord raised up and delivered from the scourges of hell ” (from Acts 2:24) while Acts 2:24 is as follows: God raised him up and delivered him from the horrors of death , so he would not remain a hostage. Polycarp and the Epistle to the Romans: Polycarp stated: “Everyone will stand before the judgment seat of Christ, and each one of us will give an account for himself” while Romans 12:14Rom 14-12: So then each one of us will give an account for himself to God. Polycarp and the First Epistle to the Corinthians: Polycarp stated: “The secrets of the heart” while Romans 12:14:_The secrets of his heart are revealed

...and he falls on his face and worships God, declaring that God is truly among you.

Something amazing, only he used the phrase (secrets of the heart) so this was considered a quote from

Romans 12:14...

http://www.greatsite.com/timeline-english-bible-history/thomas-linacre.html

| This image is in another size. Click here to view the image in its correct form. The image dimensions are 723x339. |

The reason for the disagreement is that the Vulgate was translated based on the Vatican text manuscript, which differs from the common text in many places. See

http://www.biblestudy.org/basicart/does-it-matter-which-bible-is-used-for-bible-study.html

When the Turks took Constantinople in 1453, Greek Orthodox scholars fled with copies of the original Greek New Testaments, and some of them came into Europe. Erasmus (1516) and other scholars such as Stephens (1550) printed copies of the Greek New Testament, and it became obvious that the Vulgate, based on corrupted Greek texts of the Vaticanus order , had strayed far from the Received Text

Before the Latin Vulgate there was the Old

Latin Vetus Latina or Italic.

There is no single complete copy of this Old Latin text, but there are some manuscripts that contain parts of this text that preceded Jerome's text. Bruce Metziger, an American theologian, compared a manuscript containing Luke 24:4-5 and found no fewer than twenty-seven differences. See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vetus_Latina

There was no single "Vetus Latina" Bible; There are, instead, a collection of Biblical manuscript texts that bear witness to Latin translations of Biblical passages that preceded Jerome's. [1] After comparing readings for Luke 24:4-5 in Vetus Latina manuscripts, Bruce Metzger counted "no fewer than 27 variant readings

Some Old Latin manuscripts contain all four Gospels but also contain substantial differences between them, while others are only fragments of the Gospels.

There are some Old Latin texts that seem to have aspired to greater stature or currency; several manuscripts of Old Latin Gospels exist, containing the four canonical Gospels; the several manuscripts that contain them differ significantly from one another . Other Biblical passages of the Old Latin Bible are extant only in excerpts or fragments

http://vulgate.net/old-latin-bible.html

The manuscripts are not complete:

| This image is in another size. Click here to view the image in its correct form. The image dimensions are 928x558. |

So, we summarize the position of the old Latin text:

_ There is no manuscript of the Old Latin text that contains the complete text of the Bible.

_ There are some manuscripts that contain all four Gospels, but they do not agree with each other completely _ Even manuscripts that contain a few phrases have many differences

_ There is no manuscript of the Old Latin text before the fourth century, so there is no ancient manuscript text that can be said to represent the original text of the Bible, and so Christian scholars themselves are perplexed about this issue. The Bible Researcher website says: "Now what do we say? Which text do we choose as the best? We will not choose the text of Wescott and Hort, nor the Common Text, as our correct text. All these printed texts are the product of editors who are subject to error. Neither Erasmus nor Wescott and Hort are qualified to judge (the texts) properly. So we refuse to be enslaved to the critical opinions of Erasmus or Wescott and Hort. We must look at the points of disagreement between the Greek manuscripts and the printed texts, and weigh and test the evidence carefully until we arrive at what we believe to be the truth. And frankly, when there comes a point where we do not know what a particular phrase means, we must admit it."

_ There is no manuscript of the Old Latin text before the fourth century, so there is no ancient manuscript text that can be said to represent the original text of the Bible, and so Christian scholars themselves are perplexed about this issue. The Bible Researcher website says: "Now what do we say? Which text do we choose as the best? We will not choose the text of Wescott and Hort, nor the Common Text, as our correct text. All these printed texts are the product of editors who are subject to error. Neither Erasmus nor Wescott and Hort are qualified to judge (the texts) properly. So we refuse to be enslaved to the critical opinions of Erasmus or Wescott and Hort. We must look at the points of disagreement between the Greek manuscripts and the printed texts, and weigh and test the evidence carefully until we arrive at what we believe to be the truth. And frankly, when there comes a point where we do not know what a particular phrase means, we must admit it."

http://www.bible-researcher.com/kutilek1.html

What shall we say then? Which text shall we choose as superior ? We shall choose neither the Westcott-Hort text (or its modern kinsmen) nor the textus receptus (or the majority text) as our standard text, our text of last appeal. All these printed texts are compiled or edited texts, formed on the basis of the informed (or not-so-well-informed) opinions of fallible editors . Neither Erasmus nor Westcott and Hort (nor, need we say, any other text editor or group of editors) is omniscient or perfect in reasoning and judgment. Therefore, we refuse to be enslaved to the textual criticism opinions of either Erasmus or Westcott and Hort or for that matter any other scholars, whether Nestle, Aland, Metzger, Burgon, Hodges and Farstad, or anyone else. Rather, it is better to evaluate all variants in the text of the Greek New Testament on a reading by reading basis, that is, in those places where there are divergences in the manuscripts and between printed texts, the evidence for and against each reading should be carefully and carefully examined and weighed, and the arguments of the various schools of thought considered, and only then a judgment made.

We do, or should do, this very thing in reading commentaries and theology books. We hear the evidence, consider the arguments, weigh the options, and then arrive at what we believe to be the honest truth. Can one be faulted for doing the same regarding the variants in the Greek New Testament? Our aim is to know precisely what the Apostles originally did write, this and nothing more, this and nothing else. And, frankly, just as there are times when we must honestly say, “ I simply do not know for certain what this Bible verse or passage means,” there will be (and are) places in the Greek New Testament where the evidence is not clear cut , (21) and the arguments of the various schools of thought do not distinctly favor one reading over another .

We do, or should do, this very thing in reading commentaries and theology books. We hear the evidence, consider the arguments, weigh the options, and then arrive at what we believe to be the honest truth. Can one be faulted for doing the same regarding the variants in the Greek New Testament? Our aim is to know precisely what the Apostles originally did write, this and nothing more, this and nothing else. And, frankly, just as there are times when we must honestly say, “ I simply do not know for certain what this Bible verse or passage means,” there will be (and are) places in the Greek New Testament where the evidence is not clear cut , (21) and the arguments of the various schools of thought do not distinctly favor one reading over another .

People are in great confusion

then, judging which texts are the most suitable to express the word of God is the problem of problems between biblical scholars and manuscript scholars in our modern age, and when it comes to arbitrating what we believe that what we choose is the truth, this is a real problem. Therefore, the British Times website says that the Catholic Church no longer swears by the authenticity of the Bible

then, judging which texts are the most suitable to express the word of God is the problem of problems between biblical scholars and manuscript scholars in our modern age, and when it comes to arbitrating what we believe that what we choose is the truth, this is a real problem. Therefore, the British Times website says that the Catholic Church no longer swears by the authenticity of the Bible

| This image is in another size. Click here to view the image in its correct form. The image dimensions are 929x446. |

The article says that Catholic clergy in Britain are warning their followers that they should not expect complete accuracy from the Bible, whether scientific or historical, and that some parts of the book are incorrect. End of the Times.

Quotations and quotations from the early church fathers from the New Testament

Can the Bible really be compiled from the testimonies and quotations of the fathers, as they claim?

The citations of the ancient fathers in the first centuries of Christianity are considered sources of confirmation of the authenticity of the Bible by the majority of Christian scholars, as they consider the presence of a phrase from the Bible in the writings of the ancients as support for what is stated in it, so that some claim that they can assemble the Bible from these citations. The truth is that this talk contains a lot of exaggeration, as the citations of the ancients are not suitable for such a task (reassembling the book), but why?